Displaced Topologies

The Displaced Topologies collection explores the concept of belonging to disparate cultures within the context of storytelling, ancestry, deep history, displacement, borders, and both hard and soft man-made structures, as well as records of fractures, disintegration, and rebuilding. It gathers artworks that symbolize structures, documents, and humans connected by the conditions of migration, displacement, and cultural heterogeneity.

Like most artists, I feel the pull of my cultural identity, heterogeneous as it is.

My artistic research began by questioning whether an abstract visual language could be used to express a dichotomous cultural identity, which eventually evolved into a line of inquiry centred on migration. As displaced people, how do we create a sense of home and build community in foreign places? What is the contribution of displaced people to the future?

The Displaced Topologies series aims to ponder these questions without the limitation of any one cultural gaze because I do not consider myself a Serbian artist in the Canadian diaspora or a Canadian artist with Serbian roots. Creating art in this culturally ambiguous way is my assertion that the in-between state of the displaced is neither temporary nor a place of inadequacy. It is a generative space with tremendous potential for fostering communication in the multicultural future.

Home Abroad (2023) and Morning Star (2024) are experimental artworks that paved the path for Displaced Topologies. The sewn canvas collages approach evokes a relocated kind of life where the parts may originate from different cultural worldviews, forming something new. Minimalist compositions are juxtaposed with the chaotic, galactic-looking patterns, which signify making order out of chaos, akin to making a home in the pandemonium of a displaced life. To further explore how dynamic gestures can be incorporated into the medium of canvas collage, I introduce three-dimensionality through sculpted inserts, some sunken, others distended, which raises metaphorical questions about what should remain flat, what should protrude, or recede in my cultural narratives. More broadly, considering the history of migrations, the three-dimensionality metaphorizes the agency of past worlds folded within future ones, examined from the perspective of deep history and microscopically, looking at what is present now.

Sediments of Time (2024-2025) is a group of canvas collage paintings on stretched canvases hung in a bricolage pattern. The wall of paintings is a metaphor for walls as transient structures encrusted with history. It represents the complex wall we carry within ourselves, formed by history, cultural identity, and hopes for the future. The works in this series interpret the internal displacement as dynamic, constantly folding and unfolding. I think of this work as psychological, archeological, and historical. The surface of the canvas is interrupted by tearing, fraying, and layering, evoking trauma but also breakthroughs and new perspectives. Three-dimensional forms of folded textiles are flattened into patterns through line drawing, repetition, collaging, and removing the shapes, which are positioned into a lineup of alphabet-like symbols that articulate dynamic gestures evocative of pictorial writing. The symbols appear to perform a linked dance or a ceremony. This process represents migrations as a motif rather than a singular event.

I grew up doodling on my father’s mechanical engineering textbooks and sewing clothes using patterns from my mother’s fashion magazines. As an artist, I favour compositions where the whole is made up of tailored parts, forming a structure similar to a blueprint, reflecting my need to make things work and create order out of chaos. My worldview leans towards structural symbols reminiscent of maps, archives, borders, and walls. Walls often appear in my stories. I remember walls torn down, walls I have repaired, and the walls of monuments crumbling under the sediments of history. I remember the belief in building a new world for a better future. Much happens in the world while walls go up and down unpredictably, with their unexpected influence.

The Four Buildings (2025) diptych references the roof shapes of four specific utilitarian buildings from my two homelands, suturing the distant cultures within a unified context. One pair of rooflines represents the travelling hubs I have frequented, both having the power to facilitate and disrupt migrations. The other pair represents the universities I have attended in the two countries, homes of enlightenment, disillusion, and activism. Each pair of buildings connects geographies and power structures of travel and education in Serbia and Canada in an upside-down way, as one may think of them being on opposite sides of the globe, world politics, and positions of power.

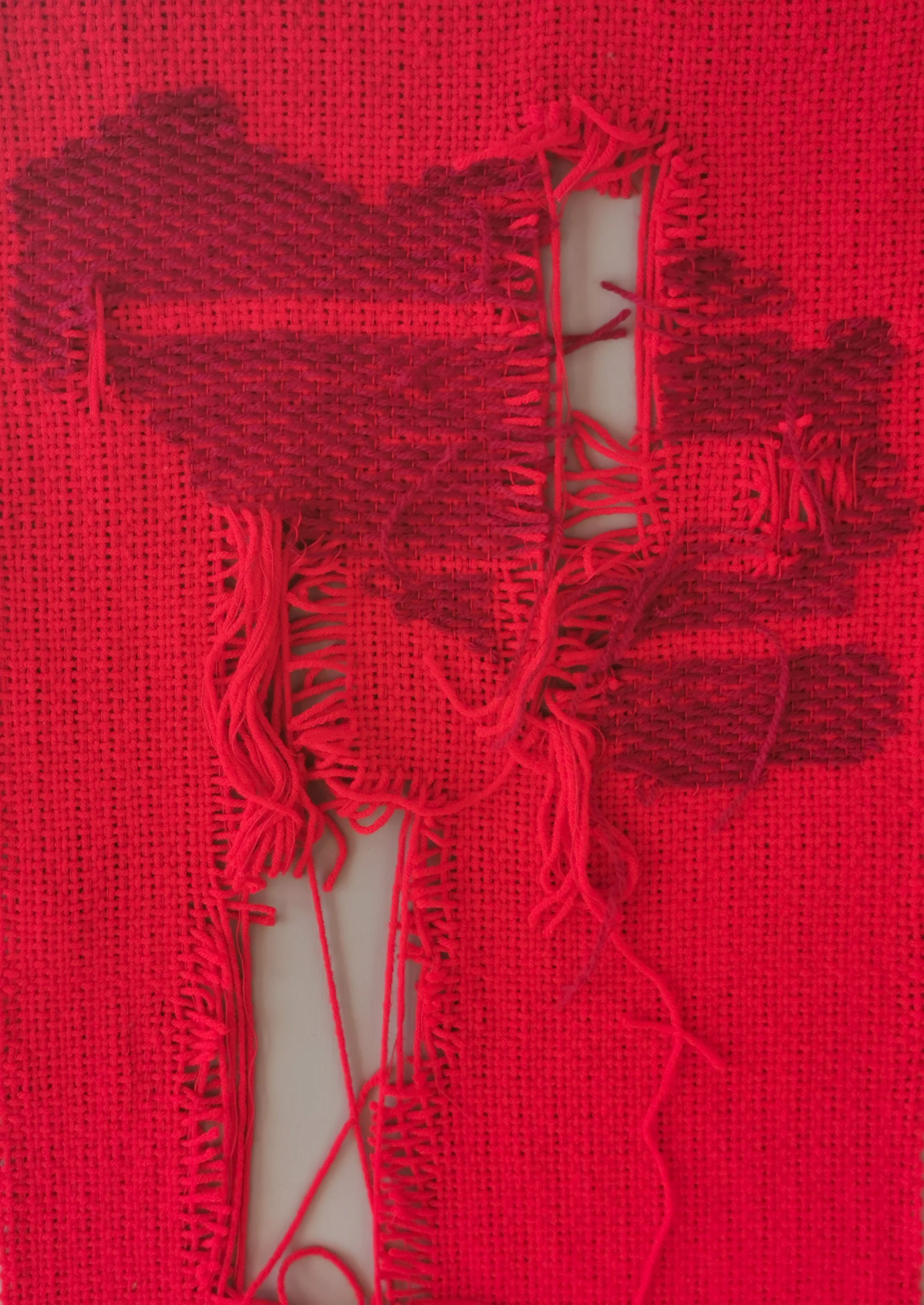

Remnants of Time (2025) is a series of woven human-sized banner-like artworks. The woven pieces with warp/weft structures manipulated by tangling, unravelling, and pooling refer to the soft structures experienced in intimate places and symbolize the management of adverse situations within ourselves. Each piece features a representation of a topography, including my torn-apart former homeland, the dry-blood-coloured land of my mother’s family, the map of my birth city on the river Danube, and the blueprints of my Serbian and Canadian homes juxtaposed as a storytelling foil. Although these woven pieces are reminiscent of political banners, scrolls, and proclamations, they embody humanity through their scale, the pooling of blood-like threads, their companionable arrangement, and their attempt to repair themselves. They anchor how one places oneself in history while showing the turmoil, shifting, and uprooting. We are all remnants of times in how we carry our locations, geologies, histories, blood and genes as our lives unfold.

Haphazard Structures (2024-2025) are mixed media drawings and embroidery on unframed raw canvas off-cuts. This body of work examines physical structures, such as buildings, and conceptual ones, such as bureaucratic structures, related to migrations. These constructs carry marks of disruptive events and slow decay that change them over time. The resulting haphazardness symbolizes the never-ending chain of destruction and rebuilding of a displaced life. While the use of frayed canvas remnants and the gesture of previously sewn and torn-off elements relate to the displacement events, the line drawings and embroidery serve as a slow, reverent observation of the cyclical making and remaking. This work historicizes lived experience and lends texture and encrustation of history to the original objects that inspired the work. The materials reflect my need for frugality and repurposing, and the scarcity mentality familiar to many migrants. The government seal on my immigration document is interpreted through unfinished embroidery, for which I used the thread from a big bag of embroidery floss remnants I inherited from my mother. This combination of materials is a symbolic continuation of the lines my mother and I used in our respective artistic practices, connecting the fragile family structure to the artwork.

My mother grew up in rural eastern Serbia, in the post-WWII poverty and enthusiasm for rebuilding the People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. Her people grappled with a complex system of beliefs, a mix of Slavic Paganism, Orthodox Christianity, and newly introduced Communism. When my mother was twelve, she was an apprentice to a healer known as the Village Witch. As a child, I pestered my mother to remember what she had learned from the healer, but all she could recall was the chant, “white thread, red thread, black thread.” There is a belief in rural Serbia that a piece of red thread tied around a baby’s hand is protection from evil spirits. Although my mother was a passionate communist and non-believer in superstitions, she was an avid sewer, knitter, crocheter, and embroiderer. The women from her family were known as excellent weavers. Where I come from, being a woman means having a deep understanding of thread crafts. I am grateful to my ancestors for passing on this beautiful and essential technology to me.

I am often asked about my life in Yugoslavia, if I am a Serb or Croat, if I condone war, if my family is well. A Canadian colleague told me about his memory of travelling to Eastern Europe, recalling it as a place full of sad, gray people. I remember my childhood as joyful and full of wonder, although the colours of my childhood home, the buildings, the clothes, and even my toys were subdued compared to what I see now in Canada. The people behaved differently in public, enacting a performative discipline that would translate as excessive sternness or sadness to an outsider. But there was the red of the communist banners, the women’s day carnations, pioneer bandanas, and roses for birthdays and anniversaries. Red was the favourite colour of my beautiful, gray people.